What CBDC Is (Not) About – Part II

The Monetary System Explained

Photo by Bruno Neurath-Wilson on Unsplash

Note: This is the second part of a series about central bank digital currencies, or CBDC (Part 1 can be found here). Please note that the post provides a simplified representation of the current monetary system that may not fully reflect the true complexity. However, this stylised model is sufficient for the purpose of our discussion which will be continued in the next post.

Tl;dr: Our monetary system can be compared to a public-private partnership where central banks and financial institutions issue euros in the form of different financial assets. A retail CBDC would introduce a new electronic form of public money that could permanently change the composition of the money supply, allow to circumvent the broken traditional money transmission mechanism, and significantly expand the influence of the central bank over the creation and management of money.

The money makers

Let's start with a (seemingly) simple question: what is money?

This innocent question turns out to be a complex philosophical endeavour that would merit its own article – or rather its own book, for that matter. For the purpose of this series, let's content ourselves with the following definition:

Money is a social system of transferable credit where underlying debit and credit relationships between users are tracked and periodically cleared.

In the absence of commodity money, all money is credit – that is, a promise by someone to 'pay' at a later date ('pay' here referring to settling a debt or obligation). In this case, simple accounting rules dictate that money also needs to be someone's liability. Who, then, can issue credit that will be used as 'money' by market participants and economic agents?

In theory, anyone. In practice, not so much.

Credit needs to be impersonal and transferable in order to circulate as money. Users need to trust the issuer to make good on the promise: the more trustworthy the issuer, the more 'money-like' their liabilities.

As we will explore in the remainder of this post, our current monetary system can be likened to a sort of public-private partnership: the public sector (i.e. central bank) creates public money, the private sector (i.e. financial institutions) creates private money.

The different forms of the euro

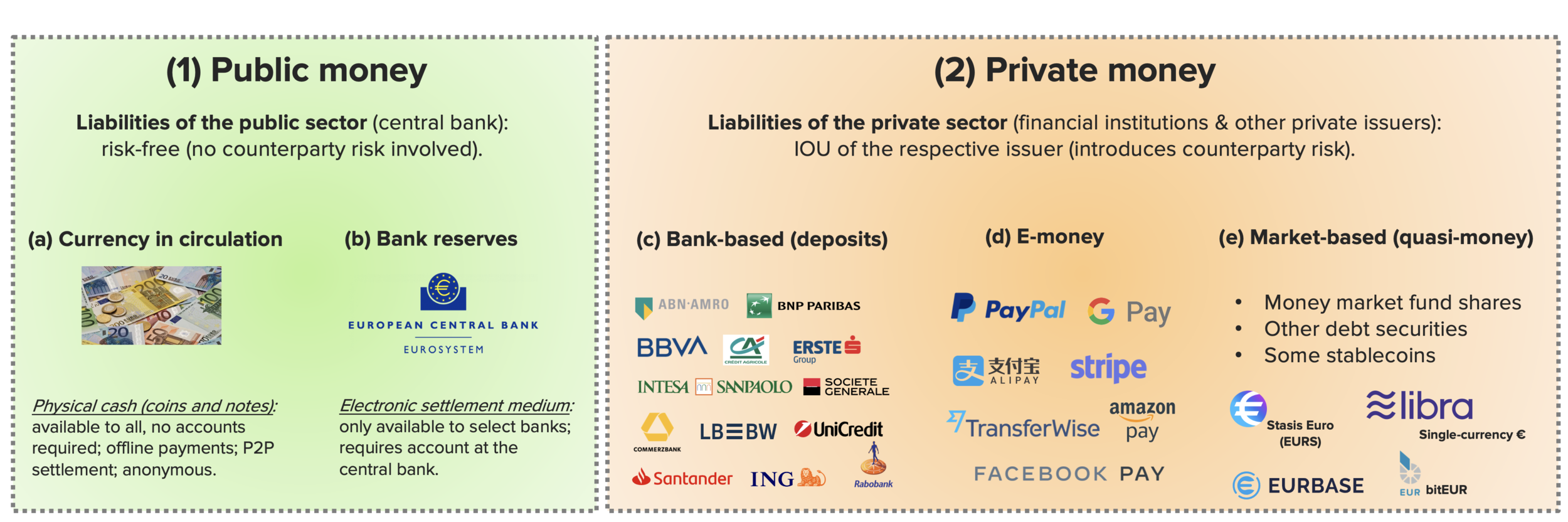

The euro – just like any other monetary system – is an abstract social phenomenon that, rather than being just one 'thing', manifests itself in different forms and shapes (see Figure 1). These forms can be divided into two broad categories, each having further subdivisions.

Figure 1: The euro in its different forms

(1) Public money: sovereign money issued by the central bank on behalf of the public sector. Public money can take the form of (a) currency in circulation, which is the physical cash (coins and notes) that is available to everyone and enjoys unique properties (e.g. bearer asset, no accounts, P2P settlement, relative transactional anonymity). Public money can also take the form of (b) bank reserves, which are electronic deposits at the central bank reserved to select commercial banks for use as a settlement medium for interbank transactions.

(2) Private money: non-sovereign money issued by various types of private financial institutions. Most money we use on a daily basis in retail (i.e. consumers and non-financial businesses) takes the form of (c) bank deposits, which are generally created by commercial banks through lending. More recently, (d) e-money issued by Electronic Money Institutions (EMI) has also established itself as a distinguished form for retail electronic payments. Finally, (e) market-based credit money is a form of private money issued by the financial sector for primary use in financial wholesale markets: it is considered quasi-money in the sense that is composed of liquid financial assets storing value (e.g. money market fund shares) that can be readily converted into a medium of exchange (e.g. bank deposits, e-money, or cash). [1]

The most important distinction between these forms of money is counterparty risk.

Public money is a liability of the central bank. If you believe in the permanent solvency of the central bank, then there is no counterparty risk associated with your claim. In this sense, public money can be considered a risk-free asset.

In contrast, private money is a liability of the private sector. And the private sector is composed of different financial institutions, each having different levels of creditworthiness and other risks. As a result, different forms of private money offer different assurances regarding the validity of claims that users hold against the issuer. As such, each instance of private money has a unique risk profile based on the issuer's credit rating – or so it seems, as we shall see soon.

The hierarchy of money

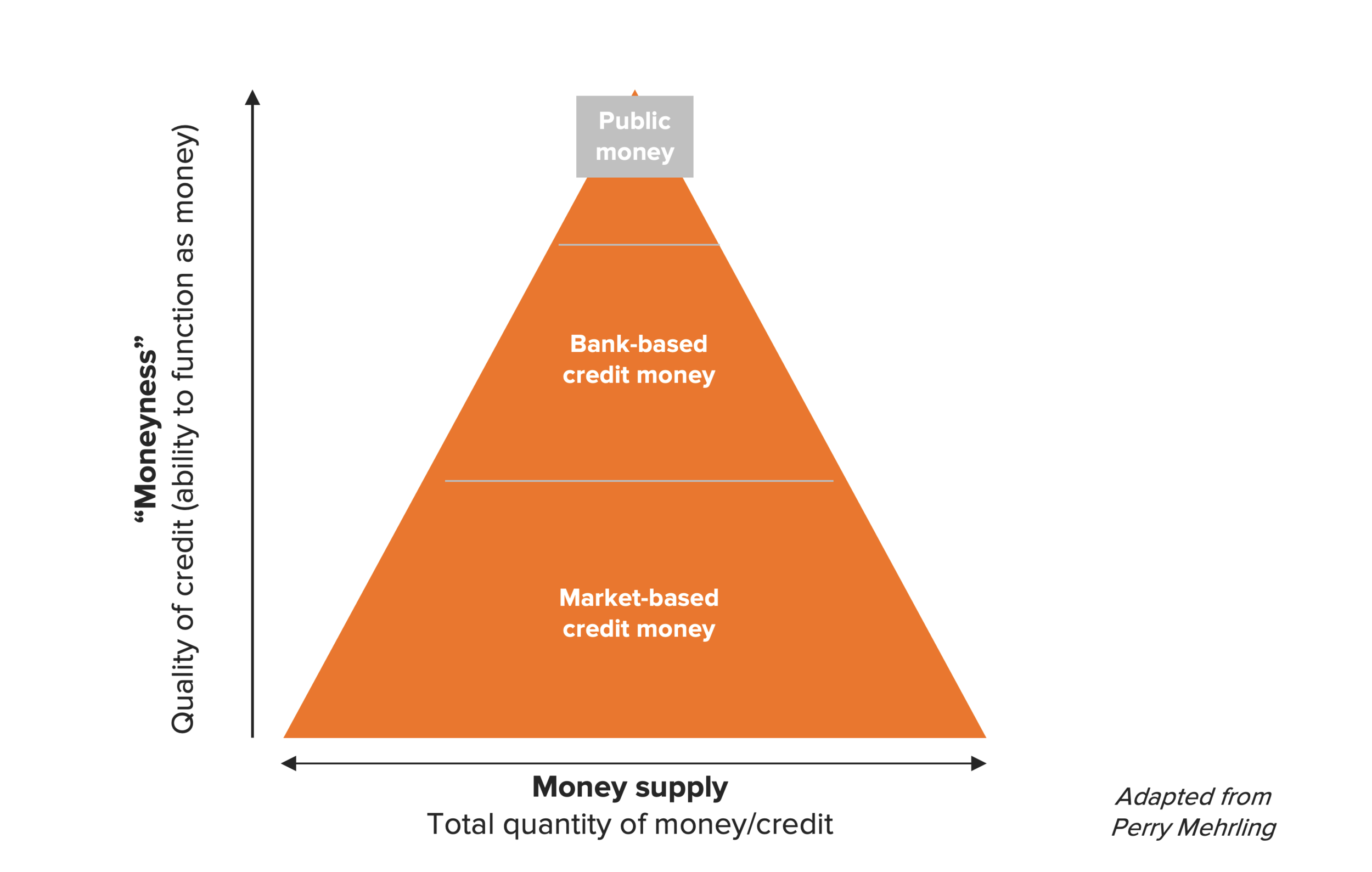

This situation gives rise to something that Perry Mehrling, professor of economics at Boston University and proponent of the "Money View", refers to as the natural hierarchy of money. It's a simple but useful model that visually represents the inherently hierarchical nature of monetary systems using a pyramid (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: The natural hierarchy of money

The x-axis denotes the total supply of money (both public and private credit) that is available to the economy and financial markets: the wider the base of the pyramid, the more money (in its various forms) is circulating overall. The y-axis indicates the degree of 'moneyness' of the different financial instruments that constitute the money supply. Moneyness here refers to the perceived quality of a given financial asset to function as money – that is, whether other market participants will accept it as money or not.

In this context, public money (also called base money) has the highest degree of moneyness: it is the most pristine version of money available on the market, and will thus always be accepted, at all times, by all market participants, for settling debts. Moving down the pyramid reveals, in descending order, the financial assets that are less likely to be permanently perceived or used as money – i.e. less 'money-like' – for a variety of reasons (e.g. higher credit and counterparty risk, limited access, etc.). [2]

In good times, when the economy is booming, this hierarchy remains mostly hidden: little difference is made between credit quality. The hierarchy only becomes apparent in times of crisis when market confidence evaporates and large amounts of private credit vanish. In that case, previously-ignored differences in credit quality suddenly materialise and lead to a 'flight to safety' (or quality): market participants are desperately trying to get their hands on forms of money that are higher up in the hierarchy.

Note: I have applied this model to digital assets (case studies include the USD and Bitcoin monetary systems) in a recent Paradigma webinar. The video is available here.

The illusion of fungibility

As we have just seen, the total money supply of an economy is composed of different types of credit – both public and private – that take various forms. But how come that we are mostly unaware of the underlying patchwork of financial assets that, despite having different issuers with no uniform credit quality, are considered equal in value?

In the context of bank-based credit money, this illusion of fungibility (thanks to Martin Walker for suggesting this apt term in a recent post) is maintained through various means, such as the willingness of central banks to act as a liquidity provider of last resort for the banking sector, or legal tender laws, or regulation. [3] The most important factor, however, are state-backed deposit protection schemes.

By guaranteeing bank deposits up to a certain value, state-backed deposit insurance conceals the underlying credit risks and ensures that deposits from different banks are considered equal and always convertible at par value. This means that, at least superficially from the perspective of consumers and businesses, a euro in the form of a bank deposit at French bank Société Générale is equivalent to a book-entry euro (i.e. in the form of a deposit) at fellow French bank Crédit Agricole. This observation can in principle be extended to the whole Eurozone area. [4]

But why would the government effectively subsidise the banking sector via guaranteed deposit insurance?

Private money creation is a feature, not a bug

The reason is simple: the banking sector (and increasingly securities markets) play a crucial role in the provision of money to the economy.

In fact, the public sector has in large parts outsourced the creation, distribution, and management of money to the private sector. Only a small share of money in circulation today is public money; the vast majority is private credit (initially mainly in the form of bank credit, but since the early 1980s increasingly in the form of market-based credit originating in the shadow banking system). [5]

This hybrid system, which has developed organically over time in a bottom-up fashion rather than being prescribed top-down, has clear advantages. It removes the burden from the central bank to be an omniscient economic institution that has to centrally manage the money supply for the economy in aggregate. Instead, it leverages the banking sector as a decentralised money creation and distribution tool.

After all, commercial banks know their customers – consumers and businesses – best. They have more direct knowledge and information about local economic conditions, and are better positioned to make informed decisions about the provision of money than any central planner ever could. As a result, private credit, intermediated via the banking sector, fulfils the important function of elasticity in the monetary system – the ability to dynamically adjust the money supply in response to changes in the demand for money by the economy.

Figure 3: Dynamic adjustment of the money supply via private sector credit

As shown by Figure 3, this hybrid system allows the total money supply to expand or contract dynamically, but in a decentralised fashion via the intermediation of financial institutions. The role of the central bank is mostly limited to setting the reference interest rate and regulating the supply of public money (mostly via operations in the open market where securities are purchased or sold in exchange for electronic bank reserves). Monetary policy conducted via these tools indirectly influences the provision of private credit – and thus the total money supply – in the economy. [6]

There is only one major problem today: it appears that this transmission mechanism is broken.

Where does CBDC fit in all of this?

In a macro environment characterised by negative interest rates and global trade collapsing, private credit money is being destroyed at a high rate throughout the system. Demand for money, on the other hand, remains high. The central bank is unable to fill that gap with new public money as part of its quantitative easing (QE) programmes, because banks aren't lending. And when banks aren't lending, newly-issued bank reserves stay within the banking system and simply end up sitting idle on banks' balance sheets. I wrote about bank reserves being similar to laundromat tokens (i.e. having little to no utility outside of a narrow area of application) a while ago, and little has changed since.

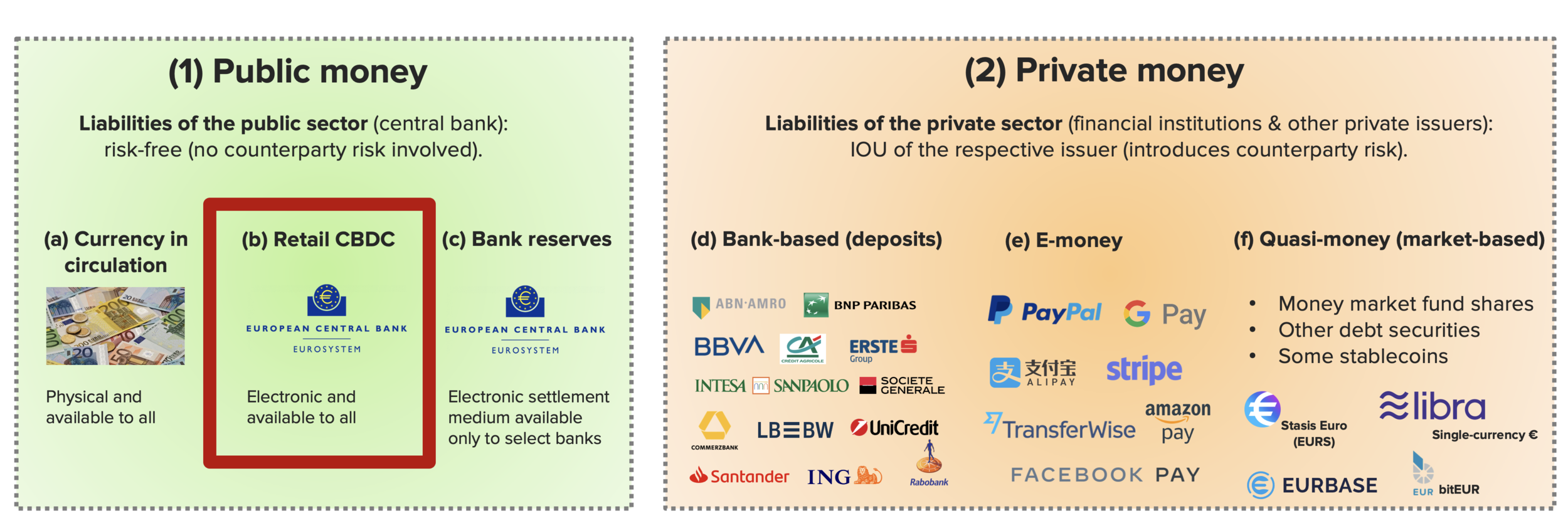

And this finally brings us to CBDC (retail CBDC, to be more precise). [7]

CBDC would introduce a new form of public money that sits in between physical currency and electronic bank reserves (see Figure 4). CBDC would be electronic, but, unlike bank reserves, not limited to a closed system of commercial banks. Instead, CBDC would be a risk-free money alternative available to all citizens and businesses alike, with no counterparty risk attached. This would provide non-banks with a direct electronic access to the balance sheet of the central bank.

Figure 4: Retail CBDC introduces a new, more accessible electronic form of public money

A retail CBDC would add a new, powerful instrument to the central bank's toolkit that otherwise seems exhausted. It would allow to circumvent the intermediation role of the banking sector by providing liquidity directly to consumers and businesses instead. [8] This development could also potentially lead to a permanent change of the composition of the money supply: public electronic money would, in large part, substitute private credit money (in particular bank deposits). As a result, CBDC would not only re-establish, but also significantly expand the central bank's influence over the total money supply.

We will explore these and other implications on the monetary system in the next post.

Footnotes

[1] Discussing the various forms of quasi-money in wholesale markets (and now also increasingly retail markets through alternative instruments such as stablecoins) is beyond the scope of this series. Market-based money creation is a complex yet fascinating subject that I would like to dive in deeper in (potential) future posts.

[2] Note that the categories themselves are not homogenous: each category can be further divided into distinct asset types (e.g. on-demand deposits vs. time deposits), and each asset type has many individual instances inheriting the creditworthiness of their issuers (e.g. a demand deposit at Deutsche Bank vs. a demand deposit at Commerzbank). In particular the category of market-based credit is very heterogenous as it encompasses promises not only of distinct credit quality, but also of distinct maturities and structuring. In reality, there are of course many more fine-grained layers and subtleties, but I find this model to be a useful conceptualisation.

[3] The picture looks a bit different for market-based credit, but suffice to say that fungibility is maintained – most of the time – through a complex system of dealers and market makers that operate in between these layers. Perry Mehrling's fantastic course on Coursera about the economics of money and banking is an excellent introduction to the subject.

[4] A caveat: the lack of a common pan-European deposit protection insurance means that each Eurozone country maintains its own deposit protection scheme, which creates potential disparities in the event of financial distress.

[5] Re-iterating a previous point: market-based credit is primarily used as an alternative form of money in wholesale financial markets. Given the retail nature of the CBDC discussed in this post, limiting the focus on bank-based credit is sufficient for our purposes.

[6] I'm simplifying quite a bit here; the goal is to highlight the importance of bank lending on the effectiveness of monetary policy.

[7] I use retail CBDC here in the broadest sense of the term, i.e. an electronic version of public money that can be directly accessed by every citizen, business, and financial institution.

[8] One way of looking at it: CBDC could turn bank reserves from limited-utility 'laundromat' tokens into useful currency that has real applications outside the banking sector.